-

توجه: در صورتی که از کاربران قدیمی ایران انجمن هستید و امکان ورود به سایت را ندارید، میتوانید با آیدی altin_admin@ در تلگرام تماس حاصل نمایید.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

مباحث عمومی هواشناسی

- شروع کننده موضوع Amir Mohsen

- تاریخ شروع

- وضعیت

- موضوع بسته شده است.

Thickness and its uses

http://weatherfaqs.org.uk/node/152

خلاصه

'Thickness' is a measure of how warm or cold a layer of the atmosphere is, usually a layer in the lowest 5 km of the troposphere; high values mean warm air, and low values mean cold air.

It would be perfectly feasible to define the average temperature of a layer in the atmosphere by calculating its mean value in degrees C (or Kelvin) between two vertical points, but an easier, practical way to measure this same mean temperature between two levels can be gained by subtracting the lower height value of the appropriate isobaric surface from the upper.

Thus one measure of thickness commonly quoted is

= height (500 hPa surface) - height (1000 hPa surface) [ for those of you, like me, too old to catch up with all the changes the world brings, millibars = hPa!, so 500 hPa is exactly the same as 500 mb. ]

In practical meteorology, the most common layers wherein thickness values are analysed and forecast are: 500-1000 hPa [ abbreviated to TT or TTHK] ; 850-1000 hPa; 700-1000 hPa; 700-850 hPa and 500-700 hPa. By subtracting the lower (height) value from the upper value, a positive number is always gained. The 500-1000 hPa value is used to define 'bulk' airmass mean temperature, and can be seen on several products available on the Web. The other 'partial' thicknesses are used for special purposes, for example, the 850-1000 hPa thickness is used for snow probability and maximum day temperature forecasting, as it more accurately defines the mean temperature of the lowest 1500 m (5000 ft) or so of the atmosphere.

Advection is simply the meteorologists word for movement of air in bulk. When we talk about warm advection, we mean that warm air replaces colder air, and vice-versa. These 'bulk' movements of air of differing temperatures can be seen very well on thickness charts, and differential advection, important in studies of stabilisation / de-stabilisation, can also be inferred by considering advection of partial thicknesses.

If you pull up thickness charts from the web, it it useful to highlight the isopleths of thickness, and work out, from either the mslp pattern, or the 500 hPa pattern, whether cold or warm advection is taking place. It should be possible with practice to find warm and cold fronts (tight thickness pattern), and areas where the thermal gradient (spacing of thickness lines) is changing - note particularly areas where developments tend to decrease spacing of thickness lines -->> increased potential for atmospheric development.

Total Thickness (500-1000 hPa) isopleths (when shown in combination with other fields) are conventionally drawn as long-dash lines, with the values either thus [540] or white numerals on a black/solid rectangle. (Where there is no conflict, i.e. the thickness isopleths are the only ones shown, then usually sold/continuous lines are used.) Certain isopleths are considered 'standard', mainly for historical reasons: They are listed hereunder, with the colour code convention used by the UK Met.Office on internal charts.

474 - red 492 - purple 510 - brown 528 - blue 546 - green 564 - red 582 - purple

Operational charts usually show isopleths at 6 dam intervals but some international forecast output will only have the standard isopleths as above: for example the UKMO 2-5 day charts. (If you want to compare forecast values over and near the British Isles with extremes, see here).

Can the 500-1000 hPa patterns be used to infer the snow risk? Well, yes they can, but because the layer is so deep -- some 5 km, or 18000 ft of the lower atmosphere, its not a good indicator. As a VERY rough guide the following may be used:

Rain and snow are equally likely when the 500-1000 hPa thickness is about 5225 gpm (or 522 dam). Rain is rare when the 500-1000 hPa thickness is less than 5190 gpm. Snow is extremely rare when the 500-1000 hPa thickness is greater than 5395 gpm.

http://weatherfaqs.org.uk/node/152

خلاصه

'Thickness' is a measure of how warm or cold a layer of the atmosphere is, usually a layer in the lowest 5 km of the troposphere; high values mean warm air, and low values mean cold air.

It would be perfectly feasible to define the average temperature of a layer in the atmosphere by calculating its mean value in degrees C (or Kelvin) between two vertical points, but an easier, practical way to measure this same mean temperature between two levels can be gained by subtracting the lower height value of the appropriate isobaric surface from the upper.

Thus one measure of thickness commonly quoted is

= height (500 hPa surface) - height (1000 hPa surface) [ for those of you, like me, too old to catch up with all the changes the world brings, millibars = hPa!, so 500 hPa is exactly the same as 500 mb. ]

In practical meteorology, the most common layers wherein thickness values are analysed and forecast are: 500-1000 hPa [ abbreviated to TT or TTHK] ; 850-1000 hPa; 700-1000 hPa; 700-850 hPa and 500-700 hPa. By subtracting the lower (height) value from the upper value, a positive number is always gained. The 500-1000 hPa value is used to define 'bulk' airmass mean temperature, and can be seen on several products available on the Web. The other 'partial' thicknesses are used for special purposes, for example, the 850-1000 hPa thickness is used for snow probability and maximum day temperature forecasting, as it more accurately defines the mean temperature of the lowest 1500 m (5000 ft) or so of the atmosphere.

Advection is simply the meteorologists word for movement of air in bulk. When we talk about warm advection, we mean that warm air replaces colder air, and vice-versa. These 'bulk' movements of air of differing temperatures can be seen very well on thickness charts, and differential advection, important in studies of stabilisation / de-stabilisation, can also be inferred by considering advection of partial thicknesses.

If you pull up thickness charts from the web, it it useful to highlight the isopleths of thickness, and work out, from either the mslp pattern, or the 500 hPa pattern, whether cold or warm advection is taking place. It should be possible with practice to find warm and cold fronts (tight thickness pattern), and areas where the thermal gradient (spacing of thickness lines) is changing - note particularly areas where developments tend to decrease spacing of thickness lines -->> increased potential for atmospheric development.

Total Thickness (500-1000 hPa) isopleths (when shown in combination with other fields) are conventionally drawn as long-dash lines, with the values either thus [540] or white numerals on a black/solid rectangle. (Where there is no conflict, i.e. the thickness isopleths are the only ones shown, then usually sold/continuous lines are used.) Certain isopleths are considered 'standard', mainly for historical reasons: They are listed hereunder, with the colour code convention used by the UK Met.Office on internal charts.

474 - red 492 - purple 510 - brown 528 - blue 546 - green 564 - red 582 - purple

Operational charts usually show isopleths at 6 dam intervals but some international forecast output will only have the standard isopleths as above: for example the UKMO 2-5 day charts. (If you want to compare forecast values over and near the British Isles with extremes, see here).

Can the 500-1000 hPa patterns be used to infer the snow risk? Well, yes they can, but because the layer is so deep -- some 5 km, or 18000 ft of the lower atmosphere, its not a good indicator. As a VERY rough guide the following may be used:

Rain and snow are equally likely when the 500-1000 hPa thickness is about 5225 gpm (or 522 dam). Rain is rare when the 500-1000 hPa thickness is less than 5190 gpm. Snow is extremely rare when the 500-1000 hPa thickness is greater than 5395 gpm.

درودي ديگر بر دوستان گل

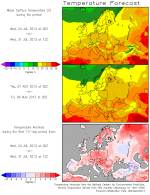

امروز هم روز گرمي واسه كل كشور خواهد بود به طوريكه براي مشهد دماي 38 و تهران 42 پيش بيني شده و اما نكته قابل ذكر اينكه واندرگراند پيش بيني دمايي دوشنبه هفته بعد را تعديل كرد و واسه مشهد و تهران حداكثر دماي 41 پيش بيني كرده!ولي در كل طي 7 روز آينده روزهاي گرمي در پيش داريم.

امروز هم روز گرمي واسه كل كشور خواهد بود به طوريكه براي مشهد دماي 38 و تهران 42 پيش بيني شده و اما نكته قابل ذكر اينكه واندرگراند پيش بيني دمايي دوشنبه هفته بعد را تعديل كرد و واسه مشهد و تهران حداكثر دماي 41 پيش بيني كرده!ولي در كل طي 7 روز آينده روزهاي گرمي در پيش داريم.

سامیار هواشناس

کاربر ويژه

تهران امروز به 42 خواهد رسید که نسبتا کم سابقست اما عبور از 42 یک رکورد کم سابقه حساب میشه اگر سایتی دمای بالای 43 برای تهران پیش بینی میکنه خودش رو بی اعتبار میکنه و خیلی بعیده که تهران از رکورد 50 سالش عبور کنه به هر حال خدا امروز رو بخیر کنه متنفرم از این روزهای جهنمی

سامیار هواشناس

کاربر ويژه

دمای مهراباد از 8:30 به 9 در ایستگاه مهراباد 2درجه کاهش یافت که به نظر میرسد اشتباه از سازمان هواشناسی باشه

هميشه شعبون يك بار هم رمضون

هميشه شعبون يك بار هم رمضون

رمضونش هم فوقش دو هفتهست!

رمضونش هم فوقش دو هفتهست!

ولي اينجا هميشه رمضونه!

- وضعیت

- موضوع بسته شده است.