Greenland Ice Sheet Melt Could Occur Yearly By 2100

- Published: May 19th, 2014

By

Brian Kahn

Follow @blkahn

In July 2012, Greenland ice sheet watchers sounded the alarm as 97 percent of the

ice sheet surface melted. It was a rare occurrence, one that left researchers puzzling over the exact causes and the likelihood it could occur again in the future.

New research released Monday sheds light on the causes behind the melt and includes projections that show if greenhouse gas emissions aren’t slowed, it could become a yearly occurrence by 2100. While that would represent a dramatic change, researchers aren’t clear what the ramifications would be.

Extent of surface melt over Greenland’s ice sheet on July 8 (left) and July 12 (right). Measurements from three satellites showed that on July 8, about 40 percent of the ice sheet had undergone thawing at or near the surface. In just a few days, the melting had dramatically accelerated and an estimated 97 percent of the ice sheet surface had thawed by July 12. Click on the image for a larger version. Credit: Nicolo E. DiGirolamo, SSAI/NASA GSFC, and Jesse Allen,

NASA Earth Observatory

The Greenland ice sheet covers an area of 656,000 square miles, roughly three times the size of Texas, in a miles-thick coat of ice. At its edges, glaciers flow into the sea and lose ice each summer. That annual melt accounts for about 30 percent of

current sea level rise.

The interior of the ice sheet is more stable as temperatures generally stay below freezing year-round and highly reflective snow sends much of the sun’s energy back to space. Temperatures did get above freezing in July 2012, but they weren’t hot enough to kickstart the

widespread melting. New research in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences shows that soot from forest fires thousands of miles away was what pushed the melt past a tipping point.

That summer, massive forest fires raged throughout Siberia, which contains the world’s largest forest. Soot from those and other fires burning in the U.S. and Canada was swept up to Greenland, settling atop the ice. The dark soot absorbed the sun’s energy, helping heat the snowpack and trigger the huge surface melt.

“We found what was needed was pretty high temperatures along with black carbon to push it over the threshold,” said Kaitlin Keegan, a postdoctoral researcher at Dartmouth University and lead author of the new study. “It looks like you need both to align to cause these widespread melting events.”

It isn't the first time a major meltdown has happened, but it is exceedingly rare. Data from ice cores indicate that the last time a melt of this magnitude occurred was in 1889 when large forest fires also deposited a layer of soot on the ice sheet. In contrast, other years with warm temperatures, notably 1868 and 1908, didn’t see a large-scale melt.

That makes such melts the equivalent of a climate jigsaw puzzle, and what Keegan and her colleagues found is that climate change is likely to make events like the July 2012 event much more common.

Using projections from the latest

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report, they modeled both temperature and wildfire changes over the 21st century. High latitude locations such as Greenland have warmed twice as fast as the rest of the globe, a trend that’s expected to continue. If greenhouse gas emissions aren’t slowed, temperatures could rise by as much as 16°F in Greenland by century’s end.

Forest fire frequency is also expected to change as the climate warms. IPCC estimates indicate that for every 1.8°F rise in temperature, forest fire frequency will double.

Using those numbers, the researchers found that the ice sheet could see widespread melting yearly by 2100. Even if emissions are curtailed and the temperature rise in the Arctic region is limited to 3.6°F, the ice sheet could still see a 2012-level melt every 6 years.

“This study represents a useful step toward predicting melt dynamics on the northern hemisphere's largest ice mass,” Joseph Cook, a glacier researcher at the University of Derby who was not involved in the study, said. “This paper adds to an ever-growing body of evidence that melt rates on the Greenland ice sheet will continue to accelerate and enhances our understanding of some of the mechanisms by which this will occur.”

Understanding the effects towards the edges of ice the sheet is a key next step, particularly what, if anything, it could mean for

sea level rise. Keegan said it’s hard to glean an answer from the current data and research available because it would be such a dramatic shift.

“We don’t know enough right now, especially a scenario where it’s melting every year. It’s really a totally different system from what we know now,” she said.

By Brian Kahn

By Brian Kahn

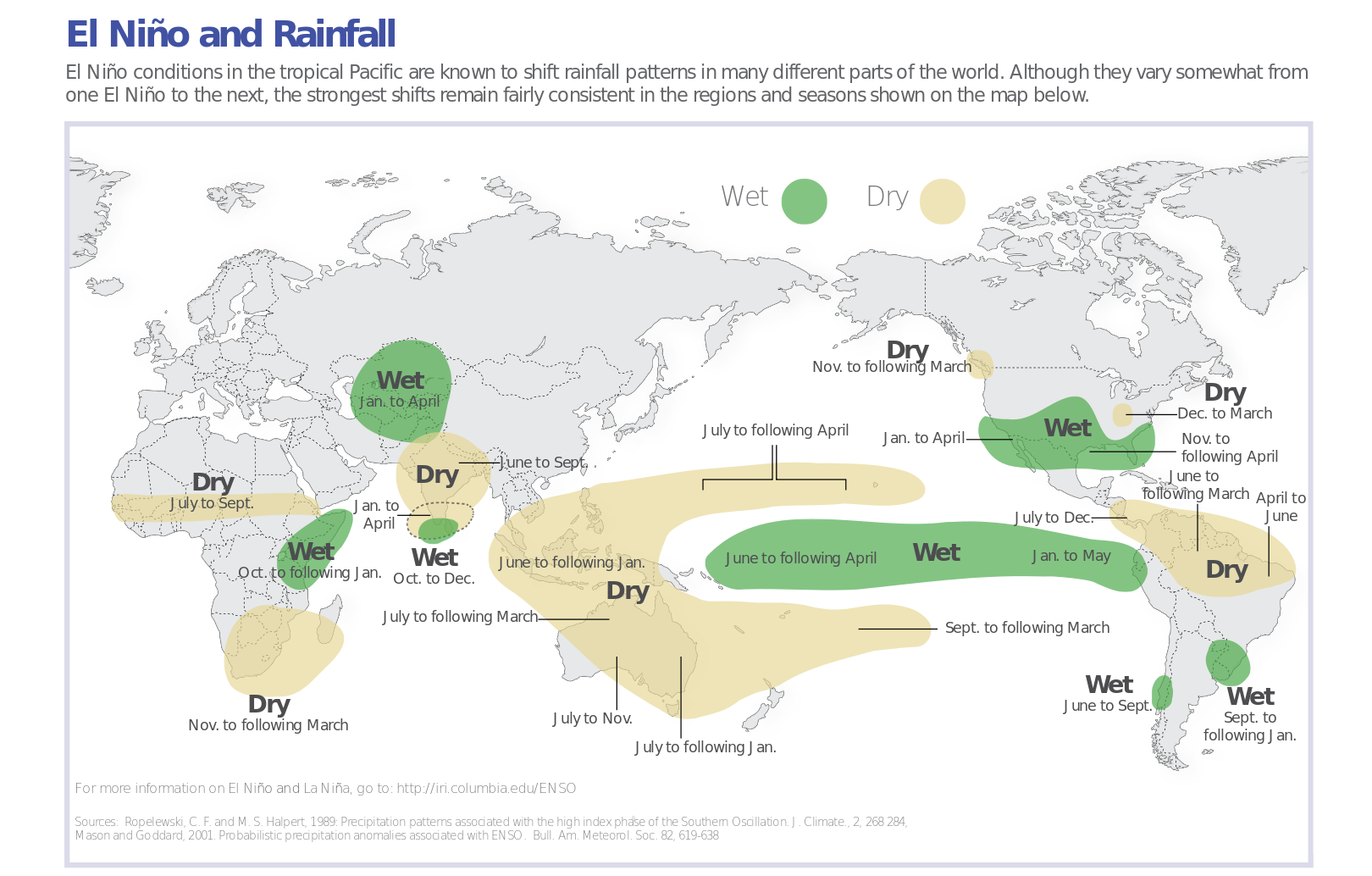

A new ScienceCast video examines the evidence that an El Niño is developing in the Pacific. Play it

A new ScienceCast video examines the evidence that an El Niño is developing in the Pacific. Play it

On May 8th, the National Centers for Environmental Prediction forecasted a 65% chance of El Niño developing during the summer of 2014. More

On May 8th, the National Centers for Environmental Prediction forecasted a 65% chance of El Niño developing during the summer of 2014. More By Danielle Wiener-Bronner 9 hours ago

By Danielle Wiener-Bronner 9 hours ago

NOW WATCHING

NOW WATCHING  UP NEXT

UP NEXT