-

توجه: در صورتی که از کاربران قدیمی ایران انجمن هستید و امکان ورود به سایت را ندارید، میتوانید با آیدی altin_admin@ در تلگرام تماس حاصل نمایید.

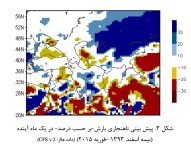

تجزیه و تحلیل وضعیت جوی در سال زراعی 93-94 /فصل دوم( دي- بهمن-اسفند)

- شروع کننده موضوع heaven1

- تاریخ شروع

- وضعیت

- موضوع بسته شده است.

سلام دوستانپس فکر کنم الینا خانوم دلیل اینکه میگفتم که بعید میدونم برف جمعه بیاد رو فهمیده باشید و همدیگر رو به ناامیدی و بی دلیل بهونه تراشی متهم نکنیم من هم صحبت هام از رو پیشبیتی ها و اون چیزی که میبینمه دقیقا مثل شما..

محمد رضا انصافا شما جز واقعیت چیز نگفتی فقط تم وزمینه حرفات تاریک و حزن انگیزه وما شما رو خیلی دوست داریم به دل نگیری

ممنون نیما جان لطف داری انشالا که تو باقی مونده زمستون بارش های خوب به انضمام یکی دوتا برف خوب کسب کنیم تا به قول شما تم ما و سایر دوستان هم عوض بشه و روحمون شاد بشهسلام دوستان

محمد رضا انصافا شما جز واقعیت چیز نگفتی فقط تم وزمینه حرفات تاریک و حزن انگیزه وما شما رو خیلی دوست داریم به دل نگیری

seyyedalireza

مدیر موقت

من نمیدونم چرا توی تمام نقشه ها قسمت مشهد بارشش بسیار کمه و حتی صفره؟ واقعا علتش چيهدکه بیست کيلوومتر اونطرف تر رو خیلی خوب میزنن ولی مشهد و نه

seyyedalireza

مدیر موقت

سامان شما شماره تو بده بیایم توی وايبرت باهم چت کنیم اینجا نمیشه داداشدلمون واسه امیر محسن تنگ شده . سایر دوستان هم کم رنگ شدن. صفحات فروم جلو نمیره

ای بابا این بی بارشی رو همه چی تاثیر گذاشته.

خیلی هم خوب...

وحید - مشهد

کاربر ويژه

سامان شما شماره تو بده بیایم توی وايبرت باهم چت کنیم اینجا نمیشه داداش

سید جان یک گروه تو وایبر بزن همه دور هم باشیم. کسی از ای سی ام خبر نداره چطور آپ کرده؟

"Polar vortex" is also a real term used by the meteorological world, but appeared to gain popularity among headline-writers last year when the US was hit with freezing temperatures. It refers to a system of upper-level winds that circle over the poles, usually helping to keep the extremely cold air in. But when the winds weaken, the shape of the vortex can become distorted and large pockets of arctic air can move away from the polar regions, causing lower than normal temperatures elsewhere. ABC News describes it as the "most misused weather term of 2014", as many people used the term to describe each new pocket of cold air. "If the actual polar vortex was moving over the United States, we would have much bigger planetary problems to cope with," it said. ·

For further concise, balanced comment and analysis on the week's news, try The Week magazine. Subscribe today and get 6 issues completely free.

Read more: Beast of the East and five other wacky weather names | weather News | The Week UK

For further concise, balanced comment and analysis on the week's news, try The Week magazine. Subscribe today and get 6 issues completely free.

Read more: Beast of the East and five other wacky weather names | weather News | The Week UK

03.02.2015 06:50 Age: 9 hrs

Click to enlarge. Weekly sea surface temperature (SST) changes. Courtesy BoM.

Click to enlarge. Monthly sea surface temperature (SST) changes. Courtesy BoM.

Click to enlarge. The sub-surface temperature map for 5 days. Courtesy BoM.

Click to enlarge. The four-month sequence of sub-surface temperature anomalies. Courtesy BoM.

Click to enlarge. The Southern Oscillation Index (SOI). Courtesy BoM.

Click to enlarge. Trade wind anomalies. Courtesy BoM.

Click to enlarge. Cloudiness near the Date Line. Courtesy BoM.

Click to enlarge. Climate models. Courtesy BoM.

Click to enlarge. Values of the Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) index. Courtesy BoM.

Conditions in the tropical Pacific have moved further away from the thresholds for an El Nino Pacific Ocean warming event, according to the latest report from the Australian Bureau of Meteorology (BoM).

This is the time when El Nino–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) events naturally fade and the pattern of sea surface temperature (SST) anomalies has remained broadly unchanged over the previous two weeks, although the anomalies have decreased slightly in the eastern half of the equatorial Pacific, says BoM.

All eight surveyed international climate models favour so called neutral values of central Pacific Ocean SSTs until at least April.

Here is the text of the latest ENSO Wrap Up analysis issued by the Australian Bureau of Meteorology today (3 February 2015) with graphics on the right.

Issued on 3 February 2015 | Product Code IDCKGEWW00

The tropical Pacific Ocean has eased away from the borderline El Niño observed during late 2014. Overall, the tropical Pacific region remains neutral.

Neutral El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) indicators include central to eastern Pacific sea surface temperatures, temperatures beneath the sea surface and cloudiness near the Date Line. The Southern Oscillation Index (SOI) has returned to near to threshold values, but this is primarily due to tropical weather activity near Tahiti rather than a broadscale climate signal. The SOI is often affected by weather phenomena during this time of the year.

The late summer to early autumn period is the time of year when ENSO events naturally decay. Forecasting beyond this time is therefore difficult, and some caution should be exercised. International models surveyed by the Bureau indicate that tropical Pacific sea surface temperatures are likely to remain within the neutral range for at least the next three months.

The pattern of sea surface temperature (SST) anomalies has remained generally similar to two weeks ago, although the anomalies have decreased slightly in the eastern half of the equatorial Pacific. The SST anomaly map for the week ending 1 February shows warm anomalies in the western tropical Pacific in much of the area west of 150°W. Temperatures are broadly near average for this time of the year in most of the equatorial Pacific east of this point.

Warm anomalies remain in small areas along the equator and across a large part of the northeast of the Pacific Basin. Waters are also warmer than average in the Tasman and Coral seas, as are waters in much of the eastern half of the Indian Ocean. This is opposite to what may be expected during an El Niño period.

The SST anomaly map for January shows warmer than average waters covering large ares of the Pacific. These areas include the tropical Pacific west of about 160°W, much of the northeast of the Pacific Basin, and waters off Australia’s east coast. Warmer waters also persist across large parts of the Indian Ocean. Compared to December, positive anomalies have decreased across most of the central and eastern equatorial Pacific, particularly east of about 160°W where anomalies were generally near zero for January.

The sub-surface temperature map for the 5 days ending 1 February shows temperatures are near average across most of the sub-surface of the equatorial Pacific, although a small area of weak warm anomalies are present just east of the Date Line at around 150 m depth.

The four-month sequence of sub-surface temperature anomalies (to January) shows that cool anomalies have increased markedly compared to last month in the sub-surface of the eastern equatorial Pacific while warm anomalies remain in the western equatorial Pacific sub-surface.

Water in much of the top 200 m of the easternn half of the equatorial sub-surface is cooler than average, with anomalies reaching more than −3 °C in part of this area. Weak warm anomalies are present in the top 100 m of the equatorial sub-surface around and west of the Date Line, and also below about 200 m in the same region.

The Southern Oscillation Index (SOI) has remained relatively stable over the past fortnight, hovering around the boundary of neutral and El Niño values. The latest 30-day SOI value to 1 February is −8.3. The recent dip in values of the SOI is primarily related to transient weather systems in the vicinity of Tahiti, and does not indicate a broadscale climate signal. It is common for tropical weather systems to cause transient fluctuations in the SOI during the first quarter of the year, especially if a tropical low or cyclone was to pass near either Darwin or Tahiti.

Sustained positive values of the SOI above +8 may indicate La Niña, while sustained negative values below −8 may indicate El Niño. Values of between about +8 and −8 generally indicate neutral conditions.

Trade winds were weaker than average over tropical Pacific around and west of the Date Line, with a reversal seen in some parts of the far western tropical Pacific where westerly winds were observed for the 5 days ending 1 February (see map). However it is worth noting that westerly wind anomalies in parts of the western tropical Pacific sometimes occur during as a normal part of the breakdown of an El Niño. Over the remainder of the central and eastern tropical Pacific trade winds were near average.

During La Niña there is a sustained strengthening of the trade winds across much of the tropical Pacific, while during El Niño there is a sustained weakening of the trade winds.

Cloudiness near the Date Line was above average for the second half of January, with recent daily values close to average.

Cloudiness along the equator, near the Date Line, is an important indicator of ENSO conditions, as it typically increases (negative OLR anomalies) near and to the east of the Date Line during El Niño and decreases (positive OLR anomalies) during La Niña.

All eight surveyed international climate models favour neutral values of central Pacific Ocean SSTs until at least April. There is some spread in model outlooks from late autumn to winter. Three models predict warming of SSTs to above El Niño threshold values by mid-winter; three models favour little change in SST anomalies; and two favour some cooling of central Pacific SSTs over autumn–winter, although remaining within neutral bounds.

This spread in model outlooks is indicative of outlooks leading into the autumn period, when the natural cycle of SST temperature tends to break down the gradient across the Pacific and hence the ocean/atmosphere reinforcement. Hence model outlooks forecast through the autumn months have lower confidence than forecasts at other times of the year. Model outlooks for predictions through autumn should therefore be treated with caution.

The latest weekly value of the Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) index to 1 February is −0.7 °C. Climate models surveyed in the model outlooks favour a continuation of a neutral phase of the IOD until at least early in the austral winter.

The IOD typically has little influence on Australian climate from December to April. During this time of year, establishment of negative or positive IOD patterns is largely inhibited by the development and position of the monsoon trough in the southern hemisphere.

Click to enlarge. Weekly sea surface temperature (SST) changes. Courtesy BoM.

Click to enlarge. Monthly sea surface temperature (SST) changes. Courtesy BoM.

Click to enlarge. The sub-surface temperature map for 5 days. Courtesy BoM.

Click to enlarge. The four-month sequence of sub-surface temperature anomalies. Courtesy BoM.

Click to enlarge. The Southern Oscillation Index (SOI). Courtesy BoM.

Click to enlarge. Trade wind anomalies. Courtesy BoM.

Click to enlarge. Cloudiness near the Date Line. Courtesy BoM.

Click to enlarge. Climate models. Courtesy BoM.

Click to enlarge. Values of the Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) index. Courtesy BoM.

Conditions in the tropical Pacific have moved further away from the thresholds for an El Nino Pacific Ocean warming event, according to the latest report from the Australian Bureau of Meteorology (BoM).

This is the time when El Nino–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) events naturally fade and the pattern of sea surface temperature (SST) anomalies has remained broadly unchanged over the previous two weeks, although the anomalies have decreased slightly in the eastern half of the equatorial Pacific, says BoM.

All eight surveyed international climate models favour so called neutral values of central Pacific Ocean SSTs until at least April.

Here is the text of the latest ENSO Wrap Up analysis issued by the Australian Bureau of Meteorology today (3 February 2015) with graphics on the right.

Issued on 3 February 2015 | Product Code IDCKGEWW00

The tropical Pacific Ocean has eased away from the borderline El Niño observed during late 2014. Overall, the tropical Pacific region remains neutral.

Neutral El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) indicators include central to eastern Pacific sea surface temperatures, temperatures beneath the sea surface and cloudiness near the Date Line. The Southern Oscillation Index (SOI) has returned to near to threshold values, but this is primarily due to tropical weather activity near Tahiti rather than a broadscale climate signal. The SOI is often affected by weather phenomena during this time of the year.

The late summer to early autumn period is the time of year when ENSO events naturally decay. Forecasting beyond this time is therefore difficult, and some caution should be exercised. International models surveyed by the Bureau indicate that tropical Pacific sea surface temperatures are likely to remain within the neutral range for at least the next three months.

The pattern of sea surface temperature (SST) anomalies has remained generally similar to two weeks ago, although the anomalies have decreased slightly in the eastern half of the equatorial Pacific. The SST anomaly map for the week ending 1 February shows warm anomalies in the western tropical Pacific in much of the area west of 150°W. Temperatures are broadly near average for this time of the year in most of the equatorial Pacific east of this point.

Warm anomalies remain in small areas along the equator and across a large part of the northeast of the Pacific Basin. Waters are also warmer than average in the Tasman and Coral seas, as are waters in much of the eastern half of the Indian Ocean. This is opposite to what may be expected during an El Niño period.

The SST anomaly map for January shows warmer than average waters covering large ares of the Pacific. These areas include the tropical Pacific west of about 160°W, much of the northeast of the Pacific Basin, and waters off Australia’s east coast. Warmer waters also persist across large parts of the Indian Ocean. Compared to December, positive anomalies have decreased across most of the central and eastern equatorial Pacific, particularly east of about 160°W where anomalies were generally near zero for January.

The sub-surface temperature map for the 5 days ending 1 February shows temperatures are near average across most of the sub-surface of the equatorial Pacific, although a small area of weak warm anomalies are present just east of the Date Line at around 150 m depth.

The four-month sequence of sub-surface temperature anomalies (to January) shows that cool anomalies have increased markedly compared to last month in the sub-surface of the eastern equatorial Pacific while warm anomalies remain in the western equatorial Pacific sub-surface.

Water in much of the top 200 m of the easternn half of the equatorial sub-surface is cooler than average, with anomalies reaching more than −3 °C in part of this area. Weak warm anomalies are present in the top 100 m of the equatorial sub-surface around and west of the Date Line, and also below about 200 m in the same region.

The Southern Oscillation Index (SOI) has remained relatively stable over the past fortnight, hovering around the boundary of neutral and El Niño values. The latest 30-day SOI value to 1 February is −8.3. The recent dip in values of the SOI is primarily related to transient weather systems in the vicinity of Tahiti, and does not indicate a broadscale climate signal. It is common for tropical weather systems to cause transient fluctuations in the SOI during the first quarter of the year, especially if a tropical low or cyclone was to pass near either Darwin or Tahiti.

Sustained positive values of the SOI above +8 may indicate La Niña, while sustained negative values below −8 may indicate El Niño. Values of between about +8 and −8 generally indicate neutral conditions.

Trade winds were weaker than average over tropical Pacific around and west of the Date Line, with a reversal seen in some parts of the far western tropical Pacific where westerly winds were observed for the 5 days ending 1 February (see map). However it is worth noting that westerly wind anomalies in parts of the western tropical Pacific sometimes occur during as a normal part of the breakdown of an El Niño. Over the remainder of the central and eastern tropical Pacific trade winds were near average.

During La Niña there is a sustained strengthening of the trade winds across much of the tropical Pacific, while during El Niño there is a sustained weakening of the trade winds.

Cloudiness near the Date Line was above average for the second half of January, with recent daily values close to average.

Cloudiness along the equator, near the Date Line, is an important indicator of ENSO conditions, as it typically increases (negative OLR anomalies) near and to the east of the Date Line during El Niño and decreases (positive OLR anomalies) during La Niña.

All eight surveyed international climate models favour neutral values of central Pacific Ocean SSTs until at least April. There is some spread in model outlooks from late autumn to winter. Three models predict warming of SSTs to above El Niño threshold values by mid-winter; three models favour little change in SST anomalies; and two favour some cooling of central Pacific SSTs over autumn–winter, although remaining within neutral bounds.

This spread in model outlooks is indicative of outlooks leading into the autumn period, when the natural cycle of SST temperature tends to break down the gradient across the Pacific and hence the ocean/atmosphere reinforcement. Hence model outlooks forecast through the autumn months have lower confidence than forecasts at other times of the year. Model outlooks for predictions through autumn should therefore be treated with caution.

The latest weekly value of the Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) index to 1 February is −0.7 °C. Climate models surveyed in the model outlooks favour a continuation of a neutral phase of the IOD until at least early in the austral winter.

The IOD typically has little influence on Australian climate from December to April. During this time of year, establishment of negative or positive IOD patterns is largely inhibited by the development and position of the monsoon trough in the southern hemisphere.

سلام و صبح دوستان بخیر

- [h=4]

امروز

15 بهمن

ساعت: 7:30

[TD="bgcolor: yellow"]

سالم(متوسط)

عدد شاخص: 90

پیش آگاهی فردا:

[/TD]

[h=6][h=4][h=6][h=4][h=6][h=6][h=6]کیفیت هوا در ایستگاه های سنجش

116

نخریسی

[TD]

108

ساختمان

[/TD]

[TD]

102

طرق

[/TD]

[TD]

50

صدف

[/TD]

[TD]

110

تقی آباد

[/TD]

[TR]

[TD]

76

ویلا

[/TD]

[TD]

50

ماشین ابزار

[/TD]

[TD]

121

خیام

[/TD]

[TD]

رسالت

[/TD]

[TD]

74

لشگر

[/TD]

[/TR]

[h=4]

[h=4]

[*]

seyyedalireza

مدیر موقت

وحيد پیام خصوصيتو چک کن. کیان دیگر هم اگه دوست دارن بیان تو ی وايبر یا واتس آپ یک گروه بزنیم البته منو احمد یک گروه تو واتس آپ زدیم.سید جان یک گروه تو وایبر بزن همه دور هم باشیم. کسی از ای سی ام خبر نداره چطور آپ کرده؟

دماهای بهاری !

وضعيت جوي استان خراسان رضوی در 24ساعت گذشتهاز ساعت 09:30 مورخ : 14/ 11 /1393 الی ساعت 09:30 مورخ 15/ 11/1393

[TD]بیشینه دما

(سانتی گراد )

[/TD]

[TD]کمینه دما

(سانتی گراد )

[/TD]

[TD]بیشینه رطوبت

%

[/TD]

[TD]کمینه رطوبت

%

[/TD]

[TD]بارش

mm

[/TD]

[TD]برف

cm

[/TD]

[TD]پدیده مهم 24 ساعت گذشته

[/TD]

[TD]هواي فعلی

[/TD]

[TD]کدایستگاه

[/TD]

[TD]نام ایستگاه

[/TD]

[TD]ردیف

[/TD]

[TR]

[TD]220

[/TD]

[TD]04

[/TD]

[TD]13.5

[/TD]

[TD]0.2-

[/TD]

[TD]89

[/TD]

[TD]36

[/TD]

[TD]0

[/TD]

[TD]0

[/TD]

[TD]_

[/TD]

[TD]کمی ابری

[/TD]

[TD]40740

[/TD]

[TD]قوچان

[/TD]

[TD]1

[/TD]

[/TR]

[TR]

[TD]330

[/TD]

[TD]05

[/TD]

[TD]12.7

[/TD]

[TD]02.1

[/TD]

[TD]98

[/TD]

[TD]68

[/TD]

[TD]0

[/TD]

[TD]0

[/TD]

[TD]_

[/TD]

[TD]صاف

[/TD]

[TD]40741

[/TD]

[TD]سرخس

[/TD]

[TD]2

[/TD]

[/TR]

[TR]

[TD]080

[/TD]

[TD]10

[/TD]

[TD]16.1

[/TD]

[TD]03.3

[/TD]

[TD]57

[/TD]

[TD]25

[/TD]

[TD]0

[/TD]

[TD]0

[/TD]

[TD]-

[/TD]

[TD]ابری

[/TD]

[TD]40743

[/TD]

[TD]سبزوار

[/TD]

[TD]3

[/TD]

[/TR]

[TR]

[TD]310

[/TD]

[TD]07

[/TD]

[TD]15.6

[/TD]

[TD]04.2

[/TD]

[TD]55

[/TD]

[TD]26

[/TD]

[TD]0

[/TD]

[TD]0

[/TD]

[TD]_

[/TD]

[TD]کمی ابری

[/TD]

[TD]40744

[/TD]

[TD]گلمکان چناران

[/TD]

[TD]4

[/TD]

[/TR]

[TR]

[TD]180

[/TD]

[TD]03

[/TD]

[TD]17.0

[/TD]

[TD]04.4

[/TD]

[TD]56

[/TD]

[TD]18

[/TD]

[TD]0

[/TD]

[TD]0

[/TD]

[TD]_

[/TD]

[TD]ابری

[/TD]

[TD]40745

[/TD]

[TD]مشهد(فرودگاه)

[/TD]

[TD]5

[/TD]

[/TR]

[TR]

[TD]030

[/TD]

[TD]05

[/TD]

[TD]14.0

[/TD]

[TD]01.5-

[/TD]

[TD]83

[/TD]

[TD]23

[/TD]

[TD]0

[/TD]

[TD]0

[/TD]

[TD]_

[/TD]

[TD]کمی ابری

[/TD]

[TD]40746

[/TD]

[TD]نیشابور

[/TD]

[TD]6

[/TD]

[/TR]

[TR]

[TD]180

[/TD]

[TD]10

[/TD]

[TD]13.1

[/TD]

[TD]01.7-

[/TD]

[TD]73

[/TD]

[TD]27

[/TD]

[TD]0

[/TD]

[TD]0

[/TD]

[TD]-

[/TD]

[TD]ابری

[/TD]

[TD]40762

[/TD]

[TD]تربت حیدریه

[/TD]

[TD]7

[/TD]

[/TR]

[TR]

[TD]260

[/TD]

[TD]03

[/TD]

[TD]15.2

[/TD]

[TD]02.6

[/TD]

[TD]61

[/TD]

[TD]25

[/TD]

[TD]0

[/TD]

[TD]0

[/TD]

[TD]_

[/TD]

[TD]کمی ابری

[/TD]

[TD]40763

[/TD]

[TD]کاشمر

[/TD]

[TD]8

[/TD]

[/TR]

[TR]

[TD]360

[/TD]

[TD]03

[/TD]

[TD]14.7

[/TD]

[TD]02.2

[/TD]

[TD]64

[/TD]

[TD]26

[/TD]

[TD]0

[/TD]

[TD]0

[/TD]

[TD]_

[/TD]

[TD]کمی ابری

[/TD]

[TD]40778

[/TD]

[TD]گناباد

[/TD]

[TD]9

[/TD]

[/TR]

[TR]

[TD]300

[/TD]

[TD]04

[/TD]

[TD]15.4

[/TD]

[TD]00.4-

[/TD]

[TD]74

[/TD]

[TD]36

[/TD]

[TD]0

[/TD]

[TD]0

[/TD]

[TD]_

[/TD]

[TD]کمی ابری

[/TD]

[TD]40806

[/TD]

[TD]تربت جام

[/TD]

[TD]10

[/TD]

[/TR]

[TR]

[TD]250

[/TD]

[TD]06

[/TD]

[TD]11.4

[/TD]

[TD]01.2

[/TD]

[TD]100

[/TD]

[TD]51

[/TD]

[TD]0

[/TD]

[TD]0

[/TD]

[TD]-

[/TD]

[TD]کمی ابری

[/TD]

[TD]40807

[/TD]

[TD]درگز

[/TD]

[TD]11

[/TD]

[/TR]

[TR]

[TD]230

[/TD]

[TD]11

[/TD]

[TD]13.2

[/TD]

[TD]05.5

[/TD]

[TD]46

[/TD]

[TD]27

[/TD]

[TD]0

[/TD]

[TD]0

[/TD]

[TD]_

[/TD]

[TD]کمی ابری

[/TD]

[TD]40825

[/TD]

[TD]فریمان

[/TD]

[TD]12

[/TD]

[/TR]

[TR]

[TD]090

[/TD]

[TD]04

[/TD]

[TD]16.9

[/TD]

[TD]02.0

[/TD]

[TD]69

[/TD]

[TD]25

[/TD]

[TD]0

[/TD]

[TD]0

[/TD]

[TD]_

[/TD]

[TD]کمی ابری

[/TD]

[TD]40837

[/TD]

[TD]خواف

[/TD]

[TD]13

[/TD]

[/TR]

[TR]

[TD]170

[/TD]

[TD]05

[/TD]

[TD]11.0

[/TD]

[TD]04.6

[/TD]

[TD]64

[/TD]

[TD]40

[/TD]

[TD]0

[/TD]

[TD]0

[/TD]

[TD]_

[/TD]

[TD]*

[/TD]

[TD]99324

[/TD]

[TD]جغتای

[/TD]

[TD]14

[/TD]

[/TR]

[TR]

[TD]120

[/TD]

[TD]06

[/TD]

[TD]16.5

[/TD]

[TD]05.9

[/TD]

[TD]48

[/TD]

[TD]23

[/TD]

[TD]0

[/TD]

[TD]0

[/TD]

[TD]_

[/TD]

[TD]کمی ابری

[/TD]

[TD]99356

[/TD]

[TD]بردسکن

[/TD]

[TD]15

[/TD]

[/TR]

[TR]

[TD]200

[/TD]

[TD]13

[/TD]

[TD]18.5

[/TD]

[TD]08.9

[/TD]

[TD]48

[/TD]

[TD]19

[/TD]

[TD]0

[/TD]

[TD]0

[/TD]

[TD]_

[/TD]

[TD]*

[/TD]

[TD]99434

[/TD]

[TD]تایباد

[/TD]

[TD]16

[/TD]

[/TR]

[TR]

[TD]100

[/TD]

[TD]03

[/TD]

[TD]16.0

[/TD]

[TD]04.6

[/TD]

[TD]

| بيشينه باد m/s |

[TD]بیشینه دما

(سانتی گراد )

[/TD]

[TD]کمینه دما

(سانتی گراد )

[/TD]

[TD]بیشینه رطوبت

%

[/TD]

[TD]کمینه رطوبت

%

[/TD]

[TD]بارش

mm

[/TD]

[TD]برف

cm

[/TD]

[TD]پدیده مهم 24 ساعت گذشته

[/TD]

[TD]هواي فعلی

[/TD]

[TD]کدایستگاه

[/TD]

[TD]نام ایستگاه

[/TD]

[TD]ردیف

[/TD]

[TR]

[TD]220

[/TD]

[TD]04

[/TD]

[TD]13.5

[/TD]

[TD]0.2-

[/TD]

[TD]89

[/TD]

[TD]36

[/TD]

[TD]0

[/TD]

[TD]0

[/TD]

[TD]_

[/TD]

[TD]کمی ابری

[/TD]

[TD]40740

[/TD]

[TD]قوچان

[/TD]

[TD]1

[/TD]

[/TR]

[TR]

[TD]330

[/TD]

[TD]05

[/TD]

[TD]12.7

[/TD]

[TD]02.1

[/TD]

[TD]98

[/TD]

[TD]68

[/TD]

[TD]0

[/TD]

[TD]0

[/TD]

[TD]_

[/TD]

[TD]صاف

[/TD]

[TD]40741

[/TD]

[TD]سرخس

[/TD]

[TD]2

[/TD]

[/TR]

[TR]

[TD]080

[/TD]

[TD]10

[/TD]

[TD]16.1

[/TD]

[TD]03.3

[/TD]

[TD]57

[/TD]

[TD]25

[/TD]

[TD]0

[/TD]

[TD]0

[/TD]

[TD]-

[/TD]

[TD]ابری

[/TD]

[TD]40743

[/TD]

[TD]سبزوار

[/TD]

[TD]3

[/TD]

[/TR]

[TR]

[TD]310

[/TD]

[TD]07

[/TD]

[TD]15.6

[/TD]

[TD]04.2

[/TD]

[TD]55

[/TD]

[TD]26

[/TD]

[TD]0

[/TD]

[TD]0

[/TD]

[TD]_

[/TD]

[TD]کمی ابری

[/TD]

[TD]40744

[/TD]

[TD]گلمکان چناران

[/TD]

[TD]4

[/TD]

[/TR]

[TR]

[TD]180

[/TD]

[TD]03

[/TD]

[TD]17.0

[/TD]

[TD]04.4

[/TD]

[TD]56

[/TD]

[TD]18

[/TD]

[TD]0

[/TD]

[TD]0

[/TD]

[TD]_

[/TD]

[TD]ابری

[/TD]

[TD]40745

[/TD]

[TD]مشهد(فرودگاه)

[/TD]

[TD]5

[/TD]

[/TR]

[TR]

[TD]030

[/TD]

[TD]05

[/TD]

[TD]14.0

[/TD]

[TD]01.5-

[/TD]

[TD]83

[/TD]

[TD]23

[/TD]

[TD]0

[/TD]

[TD]0

[/TD]

[TD]_

[/TD]

[TD]کمی ابری

[/TD]

[TD]40746

[/TD]

[TD]نیشابور

[/TD]

[TD]6

[/TD]

[/TR]

[TR]

[TD]180

[/TD]

[TD]10

[/TD]

[TD]13.1

[/TD]

[TD]01.7-

[/TD]

[TD]73

[/TD]

[TD]27

[/TD]

[TD]0

[/TD]

[TD]0

[/TD]

[TD]-

[/TD]

[TD]ابری

[/TD]

[TD]40762

[/TD]

[TD]تربت حیدریه

[/TD]

[TD]7

[/TD]

[/TR]

[TR]

[TD]260

[/TD]

[TD]03

[/TD]

[TD]15.2

[/TD]

[TD]02.6

[/TD]

[TD]61

[/TD]

[TD]25

[/TD]

[TD]0

[/TD]

[TD]0

[/TD]

[TD]_

[/TD]

[TD]کمی ابری

[/TD]

[TD]40763

[/TD]

[TD]کاشمر

[/TD]

[TD]8

[/TD]

[/TR]

[TR]

[TD]360

[/TD]

[TD]03

[/TD]

[TD]14.7

[/TD]

[TD]02.2

[/TD]

[TD]64

[/TD]

[TD]26

[/TD]

[TD]0

[/TD]

[TD]0

[/TD]

[TD]_

[/TD]

[TD]کمی ابری

[/TD]

[TD]40778

[/TD]

[TD]گناباد

[/TD]

[TD]9

[/TD]

[/TR]

[TR]

[TD]300

[/TD]

[TD]04

[/TD]

[TD]15.4

[/TD]

[TD]00.4-

[/TD]

[TD]74

[/TD]

[TD]36

[/TD]

[TD]0

[/TD]

[TD]0

[/TD]

[TD]_

[/TD]

[TD]کمی ابری

[/TD]

[TD]40806

[/TD]

[TD]تربت جام

[/TD]

[TD]10

[/TD]

[/TR]

[TR]

[TD]250

[/TD]

[TD]06

[/TD]

[TD]11.4

[/TD]

[TD]01.2

[/TD]

[TD]100

[/TD]

[TD]51

[/TD]

[TD]0

[/TD]

[TD]0

[/TD]

[TD]-

[/TD]

[TD]کمی ابری

[/TD]

[TD]40807

[/TD]

[TD]درگز

[/TD]

[TD]11

[/TD]

[/TR]

[TR]

[TD]230

[/TD]

[TD]11

[/TD]

[TD]13.2

[/TD]

[TD]05.5

[/TD]

[TD]46

[/TD]

[TD]27

[/TD]

[TD]0

[/TD]

[TD]0

[/TD]

[TD]_

[/TD]

[TD]کمی ابری

[/TD]

[TD]40825

[/TD]

[TD]فریمان

[/TD]

[TD]12

[/TD]

[/TR]

[TR]

[TD]090

[/TD]

[TD]04

[/TD]

[TD]16.9

[/TD]

[TD]02.0

[/TD]

[TD]69

[/TD]

[TD]25

[/TD]

[TD]0

[/TD]

[TD]0

[/TD]

[TD]_

[/TD]

[TD]کمی ابری

[/TD]

[TD]40837

[/TD]

[TD]خواف

[/TD]

[TD]13

[/TD]

[/TR]

[TR]

[TD]170

[/TD]

[TD]05

[/TD]

[TD]11.0

[/TD]

[TD]04.6

[/TD]

[TD]64

[/TD]

[TD]40

[/TD]

[TD]0

[/TD]

[TD]0

[/TD]

[TD]_

[/TD]

[TD]*

[/TD]

[TD]99324

[/TD]

[TD]جغتای

[/TD]

[TD]14

[/TD]

[/TR]

[TR]

[TD]120

[/TD]

[TD]06

[/TD]

[TD]16.5

[/TD]

[TD]05.9

[/TD]

[TD]48

[/TD]

[TD]23

[/TD]

[TD]0

[/TD]

[TD]0

[/TD]

[TD]_

[/TD]

[TD]کمی ابری

[/TD]

[TD]99356

[/TD]

[TD]بردسکن

[/TD]

[TD]15

[/TD]

[/TR]

[TR]

[TD]200

[/TD]

[TD]13

[/TD]

[TD]18.5

[/TD]

[TD]08.9

[/TD]

[TD]48

[/TD]

[TD]19

[/TD]

[TD]0

[/TD]

[TD]0

[/TD]

[TD]_

[/TD]

[TD]*

[/TD]

[TD]99434

[/TD]

[TD]تایباد

[/TD]

[TD]16

[/TD]

[/TR]

[TR]

[TD]100

[/TD]

[TD]03

[/TD]

[TD]16.0

[/TD]

[TD]04.6

[/TD]

[TD]