Share

Print

Ask an Expert

What is El Nino and why does it matter?

El Nino in Australia means hot sunny weather and drought. (Source: Kathryn_Thomas/iStockPhoto)

Related Stories

Extreme El Nino events set to double, Science Online, 20 Jan 2014

New forecast may predict El Nino earlier, Science Online, 02 Jul 2013

What is El Niño and why does it have so much influence over our weather?

El Niño is an ocean and atmospheric phenomenon that has a significant impact on our planet's weather.

While an El Niño event influences the whole world, the main effect is on the Pacific area, especially Australia, Indonesia and south-west America.

"During El Niño we have the droughts in western Pacific counties, like Indonesia and Australia," says Dr Wenju Cai, a senior principal research scientist at CSIRO Wealth from Oceans Flagship.

"But in other places — like Ecuador and Peru — these normally dry areas suddenly get a lot of rain. In the US, in California they experience flooding during El Niño events."

El Niño also results in a hotter average temperature for the whole planet by about 0.1 to 0.2 degrees, because the associated change in winds lead to the release of heat from the ocean to the atmosphere.

The two strongest El Niños that we know of were in 1982-83 and 1997-98. Dubbed 'super El Niños', both these events had significant global impacts.

"In 1982-83, Australia suffered one of the biggest droughts and we had the Ash Wednesday bushfires and Melbourne was covered by the dust storm," says Cai.

"In 1997, over 23,000 people were killed due to extreme events, droughts, floods, cyclones."

The 1982 El Niño caught countries around the Pacific completely unaware and prompted data gathering and research that lead to our current understanding of El Niño, says Cai.

What causes an El Niño?

Typically, an El Niño develops around May/June, strengthens through September/October and November to peak over December/January, then starts to decay in late February with weather conditions returning to normal around March.

The shift from normal — or neutral — conditions to an El Niño (or its opposite — La Niña) is governed by a complex combination of atmospheric and oceanic events.

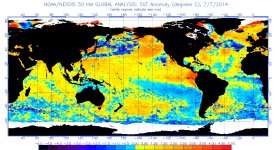

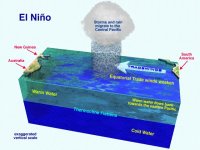

In normal conditions, an easterly trade wind blows from the Americas across the Pacific Ocean storing heat in the western Pacific. This sets up a temperature gradient — or thermocline — across the ocean with the eastern Pacific significantly colder than the western Pacific. It also creates what we consider to be normal climatic conditions — a rain band in the western Pacific, bringing rainfall to eastern Australia.

During an El Niño the temperature gradient is reduced, and the water in the eastern Pacific is warmer than normal.

But what causes an El Niño to start "is the subject of debate," says Cai.

"One of the scenarios is that a little bit of weakening in the easterly wind would make the warm water flow to the east, and once it flows to the east then the temperature gradient across the Pacific changes."

The wind may return to a normal pattern, but the ocean has a longer memory and is slower to recover. And before the ocean recovers, another weather event may occur that changes the wind again.

"An accumulation of a number of such events would then lead to a mean westerly wind developing, weakening the temperature gradient, in turn generating bigger westerly winds and a positive feedback," says Cai.

There are numerous other complex factors which come into play as well. For example, a westerly wind will suppress the Humboldt current, which runs up the west coast of Peru and Chile and normally brings an upwelling of cold water from the ocean's sub-surface to the surface.

Around this stage a tipping point is reached and the interplay between the oceans and atmosphere shifts into a different prevailing pattern, and an El Niño has formed.

What's happening now

Current indications are that we are heading towards an El Niño later in 2014 but this won't be confirmed for another couple of months.

"At the moment we're seeing the development of westerly wind and warmer temperatures in the equatorial western pacific and so that's why scientists are predicting an El Niño in the upcoming months," says Cai.

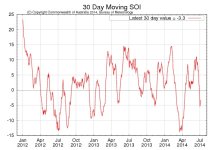

In addition to ocean temperatures and wind directions, scientists also monitor an atmospheric indicator called the Southern Oscillation Index (SOI) — which is defined as the air pressure at Tahiti minus the air pressure at Darwin, and is often reported on the news.

During an El Nino the SOI is negative because Tahiti has a lower air pressure than Darwin, and will be wetter, while Australia in the western Pacific will have a higher air pressure and be drier.

Scientists were aware of the SOI in the 1950s but the El Niño Southern Oscillation theory — ENSO —really developed following the implementation of an ocean monitoring system after the 1982 El Niño.

"The US Congress started to invest quite a lot of money putting moorings around the equatorial Pacific measuring temperature from the surface to 500 metres," says Cai.

"And that allowed us to put that information into our models to predict what is coming up in the coming months. And so the El Niño understanding of the ocean really started in the early 80s after that big El Niño."

Unfortunately, the 70 moorings or buoys that make up the ocean monitoring system are in jeopardy.

"Around four to five years ago when the US economy went downhill they decommissioned the ship that goes to service the buoys, so now the buoys are returning data at around 40 per cent. And that really is a pity because that system really revolutionised our understanding of ENSO science," says Cai.

This will make it harder to predict coming El Niños as other existing systems are not as good. However, the US has committed to build the buoys up again to a data returning rate of more than 80 per cent, says Cai.

Frequency and severity

Scientists now have a very good idea of how El Niño will be affected by climate change, says Cai, and it's not looking great.

"Under climate change the frequency of extreme El Niño events will double — to one every ten years".

The reason behind this is that the eastern equatorial Pacific Ocean — which is normally cooler than the west — is warming exceptionally fast, making it more likely that El Niños will develop.

Another important factor in understanding the severity of an El Niño in Australia is the Indian Ocean dipole, a measure of sea surface temperature difference in the Indian Ocean.

The Indian Ocean dipole, in its positive phase, features cooler than usual ocean temperatures in the eastern Indian Ocean. This results in reduced rainfall in southern Australia and south eastern Australia — and subsequently drought and bushfires.

"Our bushfires are actually preconditioned by the Indian Ocean dipole, if there is an Indian Ocean dipole then the bushfire season will be more severe," says Cai.

A positive Indian Ocean dipole often occurs with an El Niño, which can magnify the impact, although they can also occur independently.

"In 1997 we had an Indian Ocean dipole in November and in January '98 we had the biggest El Niño," says Cai.

"But there are some years when they're not related, for example in [the southern hemisphere] summer in 2007/8 we actually had La Nina years but the drought continued because we had an Indian Ocean dipole."

Unfortunately, the frequency of positive Indian Ocean dipoles is likely to triple under climate change.

Why is one side of the Pacific warming faster than the other?

As the ocean gets hotter it evaporates more, which in turn cools it down slightly — just as sweating cools down a hot person. This is called evaporative cooling, and its effectiveness increases with temperature. Adding one degree of warming to both sides of the ocean will result in more evaporative cooling on the warmer western side, effectively dampening the warming there.

"If the mean temperature in the eastern Pacific is 22 then add one degree and it becomes 23. In the western Pacific the temperature is 29, add one degree and it becomes 30 degrees — at 30 degrees the evaporation is a lot bigger than if it were 23."

So the eastern side of the Pacific is warming at a faster pace because it was colder to start with.

Dr Cai Wenju is a senior principal research scientist at CSIRO's Wealth from Oceans Flagship and leads research that is using climate change predictions to maximise agricultural, urban and ecological water use opportunities. He was interviewed by Kylie Andrews.

Tags: climate-change, weather

Published 07 July 2014

Email ABC Science

Share this article

Email a friend

Use these social-bookmarking links to share What is El Nino and why does it matter?.