By Marshall Connolly, Catholic Online (NEWS CONSORTIUM)

7/23/2014 (11 hours ago)

Catholic Online (www.catholic.org)

The expected break in California's drought is less likely to come.

Bad news for California is about to get worse. The state, wracked with drought, is eagerly anticipating the formation of a strong El Nino event in the Pacific, which would bring significant rainfall to the region. However, the El Nino may not develop as strongly as first predicted.

A sign intended to build public support for water rights for farmers now has a new significance.

Highlights

By Marshall Connolly, Catholic Online (NEWS CONSORTIUM)

Catholic Online (www.catholic.org)

7/23/2014 (11 hours ago)

Published in Green

Keywords: California, heatwave, drought, weather, severe, el nino

LOS ANGELES, CA (Catholic Online) - Most Californians are now facing the first, overdue residential water restrictions of the three year-drought that has already devastated the state. Food prices have skyrocketed in the state as well as prices on beef and dairy which are widely produced there and require at least a modicum of rainfall to produce.

Wells are plunging to record levels, then running dry as underwater supplies are slurped faster than nature can replace them. Mountain snow, which fills reservoirs, powers hydroelectric facilities and sustains agriculture is virtually all gone and there is too little left to get through another year.

Farmers have been paying attention and left their fields fallow, selling their water instead of crops.

These problems have serious impacts for the state's residents. Tourism, especially along the ski slopes, continues to suffer leaving many seasonal workers out of a job. Without reservoirs behind hydroelectric facilities, electricity production is falling off, threatening the very hot state with the potential of choosing to import electricity or suffer rolling blackouts.

Without water for crops, many fields lie fallow and agricultural workers are without jobs and income. Food prices have spiked.

The dry fields also create another problem, especially in the state's massive San Joaquin central valley - dust storms. The state has not experienced towering dust storms in nearly 40 years, but such storms can rip up topsoil and ruin fields, damage property and even kill. These storms are likely in the fall when temperatures in the Great Basin can drop and storms approach the Pacific Northwest, creating powerful pressure gradients that fuel winds channeled down the valley.

In fact, giver the macro-meteorological conditions, such a storm can almost be expected.

Californians have been in a state of denial about the drought for some time. Droughts of a few years duration aren't unheard of, but longer droughts are rare although they have happened historically.

A satellite image of California in July 2011.

The same image of California from June 24.

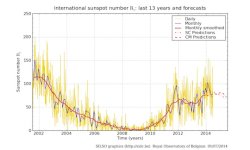

Through the spring, Californians have been eagerly following the story of the formation of a powerful El Nino in the Pacific. The warming surface waters are bad for much of the world, fueling extreme weather, but they do benefit California which is uniquely situated to receive most of the rainfall from such events.

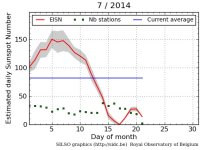

Now it seems the El Nino may be weak to moderate at best, despite its initial extreme temperatures. Scientists seem to think much of the heat from the event has already been discharged into the atmosphere. That heat has caused both May and June to be the hottest months on the planet in modern record.

However, July may be back down to more typical temperatures and the saving rains from the moderate El Nino that remains will not be enough to help California because there is another weather feature in the way - a powerful ridge of high pressure off the coast which has been blocking storms from the state, pushing them farther north than normal.

This blocking ridge of high pressure, which has remained in place for over two years, shows no sign of weakening or moving as it normally would. This ridge is also responsible for the dip in the weakening jet stream over the central USA, a phenomenon that is making the West hotter and the East colder.

Despite these significant climate abnormalities, Americans, more than any other nation in the world remain skeptical of climate change. According to a survey by Global Trends, just 54 percent think climate change is caused by humans, a slim majority. A few more agree that we are likely to see disaster if we do not reduce our emissions of greenhouse gasses such as CO2 and methane.

The high number of skeptics has a lot to do with conservative dogma, a systematic campaign of doubt fueled by corporate interests, and yes, even a hint of Protestant theology.

In China where climate change is already being widely experienced, such as during smog events in major cities such as Beijing, 93 percent of the population agrees with that climate change is being caused by humans. It makes sense, since Chinese factories are major culprits.

But the United States stands in contrast to all other nations, separated by several percentage points from England, the next-most skeptical country.

These statistics come at a time when world meteorological data proves that the planet has just endured its hottest May and June in modern history, a full 1.3 degrees higher than the 20th century average. According to NOAA climate monitoring researcher, Derek Arndt "We're living in the steroid era of the climate system. While one-twentieth of a degree doesn't sound like much, in temperature records it's like winning a horse race by several lengths."

Temperature records for every continent but Antarctica was set, although the United States had only it's 33 hottest June according to official reports. The world's oceans were also very hot, especially in the Pacific and Indian Oceans.

Whatever is going on, be it climate change, or a serious, long-term weather anomaly, California residents are in more trouble than they realize. The Union's most populous state already struggles to find water for its thirsty population and their food crops. As those supplies diminish, a genuine crisis, particularly for agriculture, may develop.

---

Pope Francis: end world hunger through 'Prayer and Action'

� 2014 - Distributed by THE NEWS CONSORTIUM

Pope Francis Prayer Intentions for July 2014

Sports: That sports may always be occasions of human fraternity and growth.

Lay Missionaries: That the Holy Spirit may support the work of the laity who proclaim the Gospel in the poorest countries.

Rosaries, Crosses, Prayer Cards and more... by Catholic Shopping .com

Marriage Blessing Holy Card

Prayer Cards

Gold Rosary Ring

Rosary

Comments

More Green

California drought likely to worsen as El Nino observed weakening Watch

By Marshall Connolly, Catholic Online (NEWS CONSORTIUM)

Bad news for California is about to get worse. The state, wracked with drought, is eagerly anticipating the formation of a strong El Nino event in the Pacific, which would bring significant rainfall to the region. However, the El Nino may not develop as strongly as ... continue reading

Bats are the super animals, science says! New study reveals that not only can these flying pest eaters see sound, but they can also see invisible light Watch

By Catholic Online (NEWS CONSORTIUM)

Polarized light may be a useful tool for bats to navigate, and the greater mouse-eared bat-Myotis myotis-is the first mammal known to navigate using polarized light. LOS ANGELES, CA (Catholic Online) - Polarized light is light waves that are parallel to each other ... continue reading

Bald eagles make a surprising comback in California! Watch

By Catholic Online (NEWS CONSORTIUM)

For the first time in more than 50 years, a nesting pair of bald eagles have been found on San Clemente Island, officials reported on July 17. LOS ANGELES, CA (Catholic Online) - This discovery means that bald eagles have re-established territories on five of the ... continue reading

TO FEED THE HUNGRY: More efficient agricultural systems could feed three billion more people Watch

By Megan Rowling, Thomson Reuters Foundation

Targeted efforts to make food systems more efficient in key parts of the world could meet the basic calorie needs of 3 billion extra people and reduce the environmental footprint of agriculture without using additional land and water, researchers said on Thursday. ... continue reading

Four wings: Amazing prehistoric raptor fossil found in China Watch

By Catholic Online (NEWS CONSORTIUM)

Since gaining popularity in the "Jurassic Park" movies, raptors, next to the Tyrannosaurus Rex, are probably the most feared dinosaur by modern man. Short and compact with razor sharp teeth and claws, their speed and agility make for real nightmare fodder. ... continue reading

Ancient flesh crawler 'resurrected' with computer generated imagery Watch

By Catholic Online (NEWS CONSORTIUM)

There would be few reasons as to why anyone would want to bring an ugly spider, long extinct, back to life. Thanks to computer generated imagery generated by fossils of a 410 million-year-old arachnid, however, scientists have been able to recreate how it ... continue reading

What is a 'zombie' weather station and why is it bad? Watch

By Marshall Connolly, Catholic Online (NEWS CONSORTIUM)

Forbes has published an article which alleges that U.S. climate scientists have manipulated climate data, using "zombie" weather stations that did not exist and "estimating" temperature data there. The article also states that a standardized network of NOAA monitoring ... continue reading

Despite climate change -- Antarctic sea ice hits second all-time record in a week Watch

By Catholic Online (NEWS CONSORTIUM)

The given notion is that Arctic ice is melting, sending levels of seawater over their usual levels. However - Arctic ice INCREASED to an all-time high in a week. Why is this? Mark Serreze, director of the National Snow and Ice Data Center says that somehow ... continue reading

Watch out! This Brazilian snake can melt a man's flesh Watch

By Catholic Online (NEWS CONSORTIUM)

A 4.6 million square foot island located 20 miles off the coast of Brazil is the only place on earth where the terrifyingly deadly golden lancehead viper can be found. LOS ANGELES, CA (Catholic Online) - Nicknamed "Snake Island", Ilha de Queimada Grande is off ... continue reading

Yosemite National Park celebrates its 150th birthday Watch

By Catholic Online (NEWS CONSORTIUM)

Visited by people from around the world, Yosemite National Park marked its 150th anniversary this week. The park has been in existence ever since 16th American President Abraham Lincoln signed an act protecting the park for generations of visitors. LOS ANGELES, ... continue reading

7/23/2014 (11 hours ago)

Catholic Online (www.catholic.org)

The expected break in California's drought is less likely to come.

Bad news for California is about to get worse. The state, wracked with drought, is eagerly anticipating the formation of a strong El Nino event in the Pacific, which would bring significant rainfall to the region. However, the El Nino may not develop as strongly as first predicted.

A sign intended to build public support for water rights for farmers now has a new significance.

Highlights

By Marshall Connolly, Catholic Online (NEWS CONSORTIUM)

Catholic Online (www.catholic.org)

7/23/2014 (11 hours ago)

Published in Green

Keywords: California, heatwave, drought, weather, severe, el nino

LOS ANGELES, CA (Catholic Online) - Most Californians are now facing the first, overdue residential water restrictions of the three year-drought that has already devastated the state. Food prices have skyrocketed in the state as well as prices on beef and dairy which are widely produced there and require at least a modicum of rainfall to produce.

Wells are plunging to record levels, then running dry as underwater supplies are slurped faster than nature can replace them. Mountain snow, which fills reservoirs, powers hydroelectric facilities and sustains agriculture is virtually all gone and there is too little left to get through another year.

Farmers have been paying attention and left their fields fallow, selling their water instead of crops.

These problems have serious impacts for the state's residents. Tourism, especially along the ski slopes, continues to suffer leaving many seasonal workers out of a job. Without reservoirs behind hydroelectric facilities, electricity production is falling off, threatening the very hot state with the potential of choosing to import electricity or suffer rolling blackouts.

Without water for crops, many fields lie fallow and agricultural workers are without jobs and income. Food prices have spiked.

The dry fields also create another problem, especially in the state's massive San Joaquin central valley - dust storms. The state has not experienced towering dust storms in nearly 40 years, but such storms can rip up topsoil and ruin fields, damage property and even kill. These storms are likely in the fall when temperatures in the Great Basin can drop and storms approach the Pacific Northwest, creating powerful pressure gradients that fuel winds channeled down the valley.

In fact, giver the macro-meteorological conditions, such a storm can almost be expected.

Californians have been in a state of denial about the drought for some time. Droughts of a few years duration aren't unheard of, but longer droughts are rare although they have happened historically.

A satellite image of California in July 2011.

The same image of California from June 24.

Through the spring, Californians have been eagerly following the story of the formation of a powerful El Nino in the Pacific. The warming surface waters are bad for much of the world, fueling extreme weather, but they do benefit California which is uniquely situated to receive most of the rainfall from such events.

Now it seems the El Nino may be weak to moderate at best, despite its initial extreme temperatures. Scientists seem to think much of the heat from the event has already been discharged into the atmosphere. That heat has caused both May and June to be the hottest months on the planet in modern record.

However, July may be back down to more typical temperatures and the saving rains from the moderate El Nino that remains will not be enough to help California because there is another weather feature in the way - a powerful ridge of high pressure off the coast which has been blocking storms from the state, pushing them farther north than normal.

This blocking ridge of high pressure, which has remained in place for over two years, shows no sign of weakening or moving as it normally would. This ridge is also responsible for the dip in the weakening jet stream over the central USA, a phenomenon that is making the West hotter and the East colder.

Despite these significant climate abnormalities, Americans, more than any other nation in the world remain skeptical of climate change. According to a survey by Global Trends, just 54 percent think climate change is caused by humans, a slim majority. A few more agree that we are likely to see disaster if we do not reduce our emissions of greenhouse gasses such as CO2 and methane.

The high number of skeptics has a lot to do with conservative dogma, a systematic campaign of doubt fueled by corporate interests, and yes, even a hint of Protestant theology.

In China where climate change is already being widely experienced, such as during smog events in major cities such as Beijing, 93 percent of the population agrees with that climate change is being caused by humans. It makes sense, since Chinese factories are major culprits.

But the United States stands in contrast to all other nations, separated by several percentage points from England, the next-most skeptical country.

These statistics come at a time when world meteorological data proves that the planet has just endured its hottest May and June in modern history, a full 1.3 degrees higher than the 20th century average. According to NOAA climate monitoring researcher, Derek Arndt "We're living in the steroid era of the climate system. While one-twentieth of a degree doesn't sound like much, in temperature records it's like winning a horse race by several lengths."

Temperature records for every continent but Antarctica was set, although the United States had only it's 33 hottest June according to official reports. The world's oceans were also very hot, especially in the Pacific and Indian Oceans.

Whatever is going on, be it climate change, or a serious, long-term weather anomaly, California residents are in more trouble than they realize. The Union's most populous state already struggles to find water for its thirsty population and their food crops. As those supplies diminish, a genuine crisis, particularly for agriculture, may develop.

---

Pope Francis: end world hunger through 'Prayer and Action'

� 2014 - Distributed by THE NEWS CONSORTIUM

Pope Francis Prayer Intentions for July 2014

Sports: That sports may always be occasions of human fraternity and growth.

Lay Missionaries: That the Holy Spirit may support the work of the laity who proclaim the Gospel in the poorest countries.

Rosaries, Crosses, Prayer Cards and more... by Catholic Shopping .com

Marriage Blessing Holy Card

Prayer Cards

Gold Rosary Ring

Rosary

Comments

More Green

California drought likely to worsen as El Nino observed weakening Watch

By Marshall Connolly, Catholic Online (NEWS CONSORTIUM)

Bad news for California is about to get worse. The state, wracked with drought, is eagerly anticipating the formation of a strong El Nino event in the Pacific, which would bring significant rainfall to the region. However, the El Nino may not develop as strongly as ... continue reading

Bats are the super animals, science says! New study reveals that not only can these flying pest eaters see sound, but they can also see invisible light Watch

By Catholic Online (NEWS CONSORTIUM)

Polarized light may be a useful tool for bats to navigate, and the greater mouse-eared bat-Myotis myotis-is the first mammal known to navigate using polarized light. LOS ANGELES, CA (Catholic Online) - Polarized light is light waves that are parallel to each other ... continue reading

Bald eagles make a surprising comback in California! Watch

By Catholic Online (NEWS CONSORTIUM)

For the first time in more than 50 years, a nesting pair of bald eagles have been found on San Clemente Island, officials reported on July 17. LOS ANGELES, CA (Catholic Online) - This discovery means that bald eagles have re-established territories on five of the ... continue reading

TO FEED THE HUNGRY: More efficient agricultural systems could feed three billion more people Watch

By Megan Rowling, Thomson Reuters Foundation

Targeted efforts to make food systems more efficient in key parts of the world could meet the basic calorie needs of 3 billion extra people and reduce the environmental footprint of agriculture without using additional land and water, researchers said on Thursday. ... continue reading

Four wings: Amazing prehistoric raptor fossil found in China Watch

By Catholic Online (NEWS CONSORTIUM)

Since gaining popularity in the "Jurassic Park" movies, raptors, next to the Tyrannosaurus Rex, are probably the most feared dinosaur by modern man. Short and compact with razor sharp teeth and claws, their speed and agility make for real nightmare fodder. ... continue reading

Ancient flesh crawler 'resurrected' with computer generated imagery Watch

By Catholic Online (NEWS CONSORTIUM)

There would be few reasons as to why anyone would want to bring an ugly spider, long extinct, back to life. Thanks to computer generated imagery generated by fossils of a 410 million-year-old arachnid, however, scientists have been able to recreate how it ... continue reading

What is a 'zombie' weather station and why is it bad? Watch

By Marshall Connolly, Catholic Online (NEWS CONSORTIUM)

Forbes has published an article which alleges that U.S. climate scientists have manipulated climate data, using "zombie" weather stations that did not exist and "estimating" temperature data there. The article also states that a standardized network of NOAA monitoring ... continue reading

Despite climate change -- Antarctic sea ice hits second all-time record in a week Watch

By Catholic Online (NEWS CONSORTIUM)

The given notion is that Arctic ice is melting, sending levels of seawater over their usual levels. However - Arctic ice INCREASED to an all-time high in a week. Why is this? Mark Serreze, director of the National Snow and Ice Data Center says that somehow ... continue reading

Watch out! This Brazilian snake can melt a man's flesh Watch

By Catholic Online (NEWS CONSORTIUM)

A 4.6 million square foot island located 20 miles off the coast of Brazil is the only place on earth where the terrifyingly deadly golden lancehead viper can be found. LOS ANGELES, CA (Catholic Online) - Nicknamed "Snake Island", Ilha de Queimada Grande is off ... continue reading

Yosemite National Park celebrates its 150th birthday Watch

By Catholic Online (NEWS CONSORTIUM)

Visited by people from around the world, Yosemite National Park marked its 150th anniversary this week. The park has been in existence ever since 16th American President Abraham Lincoln signed an act protecting the park for generations of visitors. LOS ANGELES, ... continue reading