Great Arctic Cyclone in Summer ‘Unprecedented’: Study

- Published: December 27th, 2012

208 47 63 0

By

Michael D. Lemonick

Follow @MLemonick

It’s known as the Great Arctic Cyclone, and when it roared out of Siberia last August, storm watchers knew it was unusual. Hurricane-like storms are

very common in the Arctic, but the most powerful of them (which are still far less powerful than tropical hurricanes) tend to come in winter. It wasn’t clear at the time, however, whether the August storm was truly unprecedented.

Now it is. A study published in

Geophysical Research Letters looks at no fewer than 19,625 Arctic storms and concludes that in terms of size, duration and several other of what the authors call “key cyclone properties,” the Great Cyclone was the most extreme summer storm, and the 13[SUP]th[/SUP] most powerful storm -- summer or winter -- since modern satellite observations began in 1979.

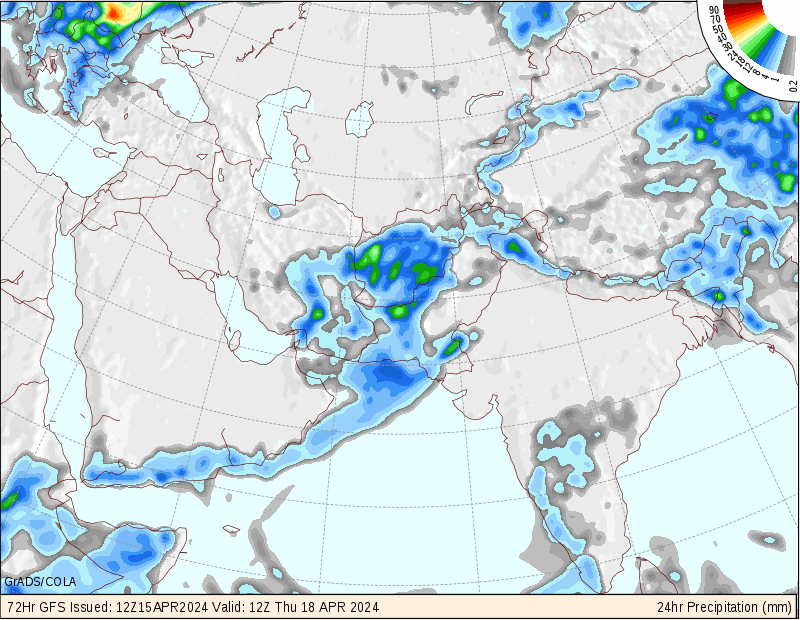

An unusually strong storm formed off the coast of Alaska on August 5 and tracked into the center of the Arctic Ocean, where it slowly dissipated.

Click to enlarge image. Credit: NASA

Although it came

during a season when Arctic sea ice was plunging toward its lowest levels on record, the authors couldn’t establish that the unusually large areas of open ocean contributed to the storm’s intensity.

On the flip side, they do argue that the storm contributed significantly to the breakup of the ice, and ultimately, to the

record-low minimum extent of sea ice covering the Arctic.

There’s at least circumstantial evidence to support this assertion: the rate of ice loss across the Arctic Ocean in August was unusually rapid, and it’s plausible to think that the churning action of the Great Cyclone helped fragment the already thin ice, letting it melt or disperse more easily.

But in the storm’s immediate aftermath, some experts argued that the ice would have vanished in any case.

“The place with the biggest loss was the East Siberian Sea, where the ice was already poised to go,” Mark Serreze, director of the

National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) in Boulder, Colo.,

told Climate Central in August when Arctic sea ice was on pace for a record low. And in an email sent the day after Christmas, Serreze reiterated his doubts. “I’m still skeptical that it had a big effect. I think there will be a paper or two on this coming out fairly soon and I would be surprised if they conclude otherwise.”

As for the storm itself, it’s reasonable to wonder

if climate change more broadly, if not the loss of sea ice in particular, was a factor in its surprising intensity. On that score, the evidence may be more than circumstantial. Arctic experts say the region has entered a

“new normal” in terms of snow and ice cover, and perhaps

of weather patterns as well.

Those weather patterns may already be having ripple effects further south in the form of

colder, snowier winters in the U.S. and Europe, at least some of the time. And in a

2004 paper, scientists concluded that Arctic cyclones increased in both number and intensity during the second half of the 20[SUP]th[/SUP] century;

another study, published in 2009, projected an increase in the number and intensity of summer cyclones by the 2100.

For Arctic storms, as for so many other climate-related events, including

droughts, heat waves and killer storm surges, the term “unprecedented” is likely to be getting quite a workout over coming decades.